Table of Contents

ToggleWhat is infographics ?

Computer graphics refers to the creation of computer-aided digital images. Unsurprisingly, it took off in the 1940s, with the development of the computer, thanks to which it gradually became possible to draw lines, add colors, create gradients, etc. are then created, at first rudimentary and then increasingly complex. From the 1990s, thanks to the simplification of digital tools, computer graphics artists, first engineers and designers of graphic tools on computers, were supplanted by a new type of graphic designer: digital artists, graphic designers now able to use computers for visual creations or image processing.

Ordinateur Amiga, par Commodore International, 1987

Today, the computer graphics designer is an image and IT specialist, able to use specific software and tools: Computer Aided Design and Publishing (CAD and DTP), vector drawing, image editing. , website creation, production of digital cartoons, colorization of comics, advertising, creation of a visual identity, creation of video games, use of 3D in architecture, animated films and images of synthesis, etc.

More broadly, computer graphics concern any type of explanatory diagram intended to present data or concepts through images. Communicators have always used computer graphics to avoid texts that are too long, off-putting and which fail to capture the public eye. Computer graphics have proven to be a particularly valuable asset in scientific communications, and in particular in the popularization of science. Science is renowned for being a difficult discipline, not accessible to the general public. Popularizing science in order to understand its most complex concepts is therefore a real challenge.

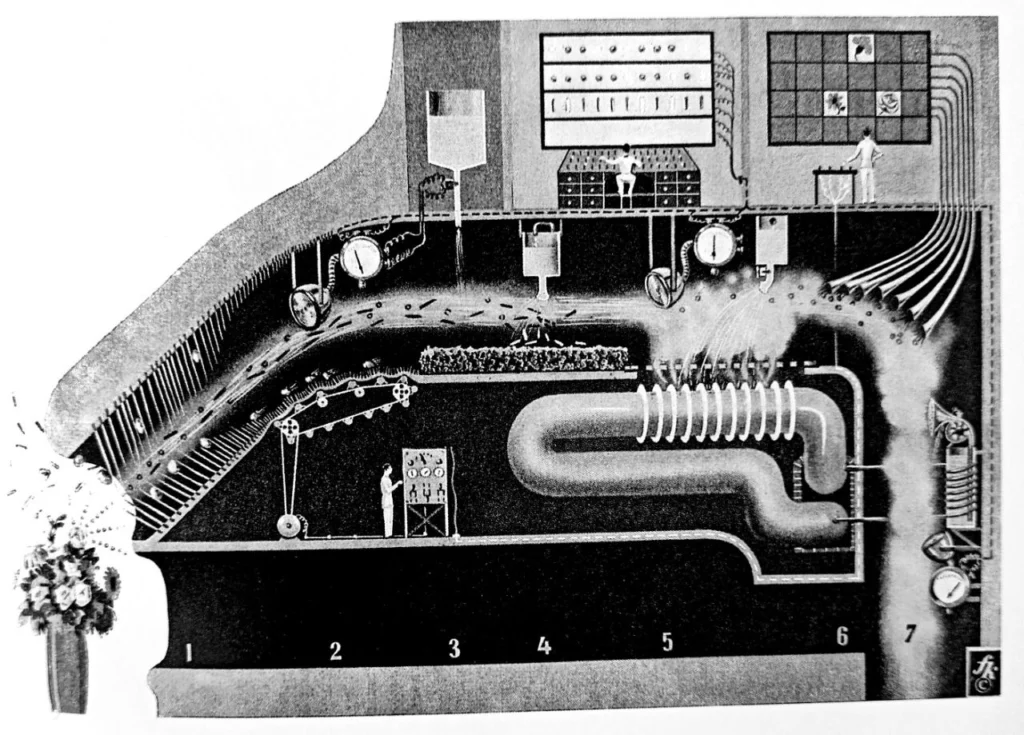

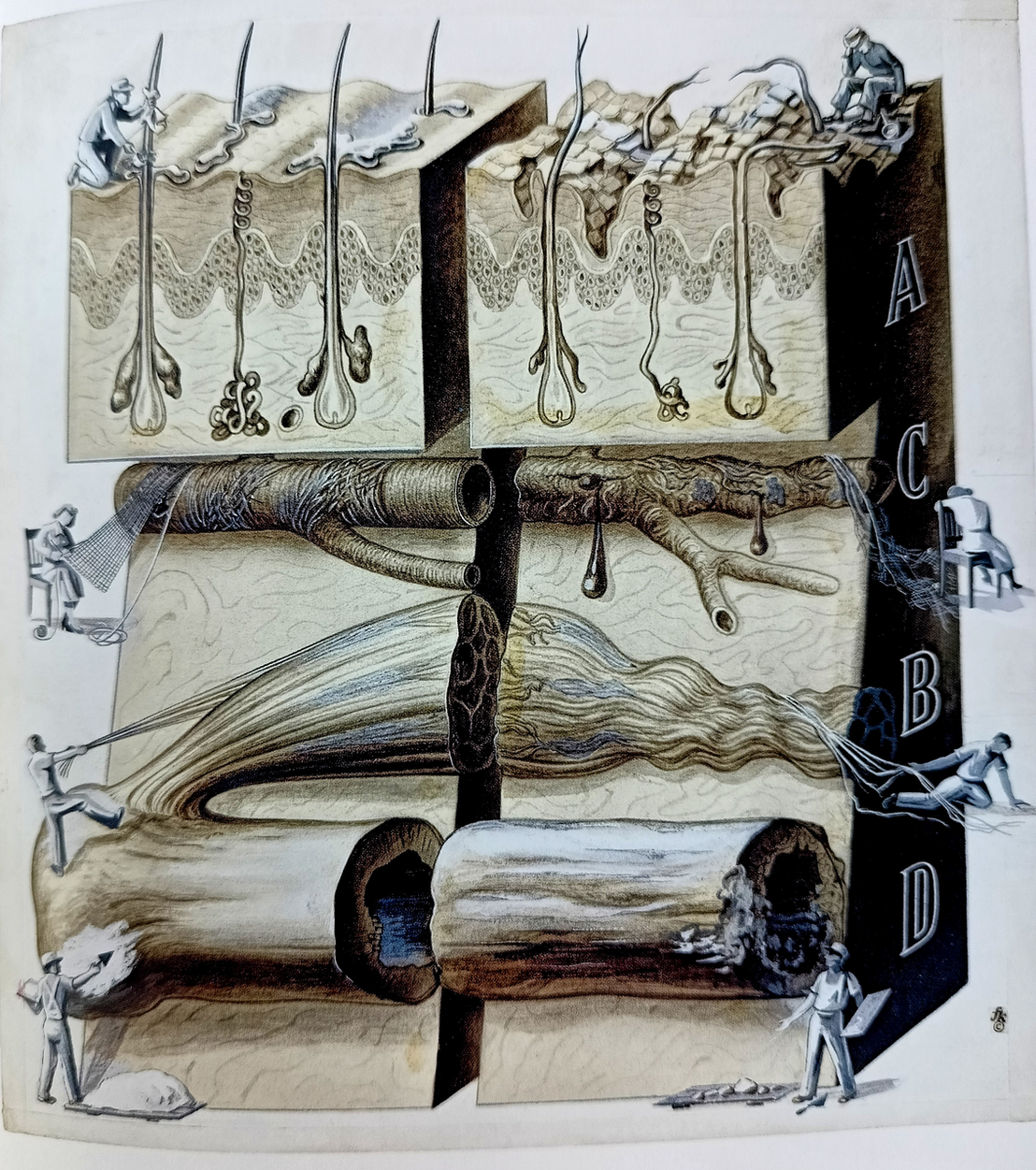

L’usage de métaphores et d’analogies est un passage obligé pour comprendre les mécanismes complexes qui gouvernent notre vie de tous les jours. Et Fritz Kahn l’a bien compris. Dans son ouvrage sur le corps humain intitulé L’Homme comme Palais de l’Industrie (1926), Fritz transforme le corps humain en usine mécanisée, où tout phénomène biologique trouve une analogie dans l’industrie et la mécanique: les yeux sont apparentés à un appareil photo, les poumons sont faits de tubes de cuivre, l’estomac et l’intestins à des tapis roulants à suspensions hydrauliques (un bon exercice pour tester notre compréhension de ces concepts pourrait être de moderniser toutes ces comparaisons avec nos technologies actuelles!).

Avant-garde and daring in his choices of analogy, Fritz Kahn has inspired generations of artists and communicators until today. But who is he really?

But who is this Fritz Kahn?

A German Jewish doctor with a life punctuated by the two world wars, Fritz is part of that generation of unfortunate men and women, born too early or too late, who spent an adult life spanning two world wars.

Like father, like son!

Born in 1888 in Germany to a German Jewish family, his family emigrated to New York quite early for his father’s work. They will stay there for about ten years before returning to Germany, to Berlin. The father was himself a doctor and a writer, and as was customary at the time, Fritz set out on the same path as his father.

Fritz Kahn et ses parents, Berlin, 1914

It was in Berlin that at 19, Fritz began studying human medicine at the Berlin University of Liberal Sciences and Arts (at the time, science and art were not yet separate disciplines as they are today. ‘hui: to learn more about this, you can refer to this article). Thanks to his various scientific publications, Fritz is already beginning to gain a reputation as a scientific writer.

Being graduated in 1914

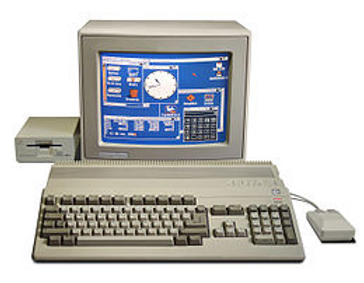

Fritz Kahn, Berlin, 1914

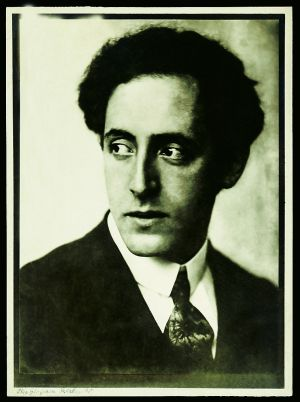

In 1914, aged 26, Fritz graduated: doctor of medicine, he began his career as a gynecologist and surgeon in a private clinic in Berlin. The First World War broke out, and Fritz enlisted as a military doctor, which did not prevent him from having a little free time to continue writing. During these years, he published two books: Die Milchstrasse (La Voie Lactée) and Die Zelle (La Cellule). After the war and a stay in Algeria, Fritz returned to work in Berlin, still as a doctor and writer. As an increasingly violent anti-Semitism grows, Fritz publishes a provocative work entitled Die Juden Als Rasse Und Kulturvolk (The Jews as a Race and Cultivated People). We had to dare! His various works are already widely published and translated all over the world.

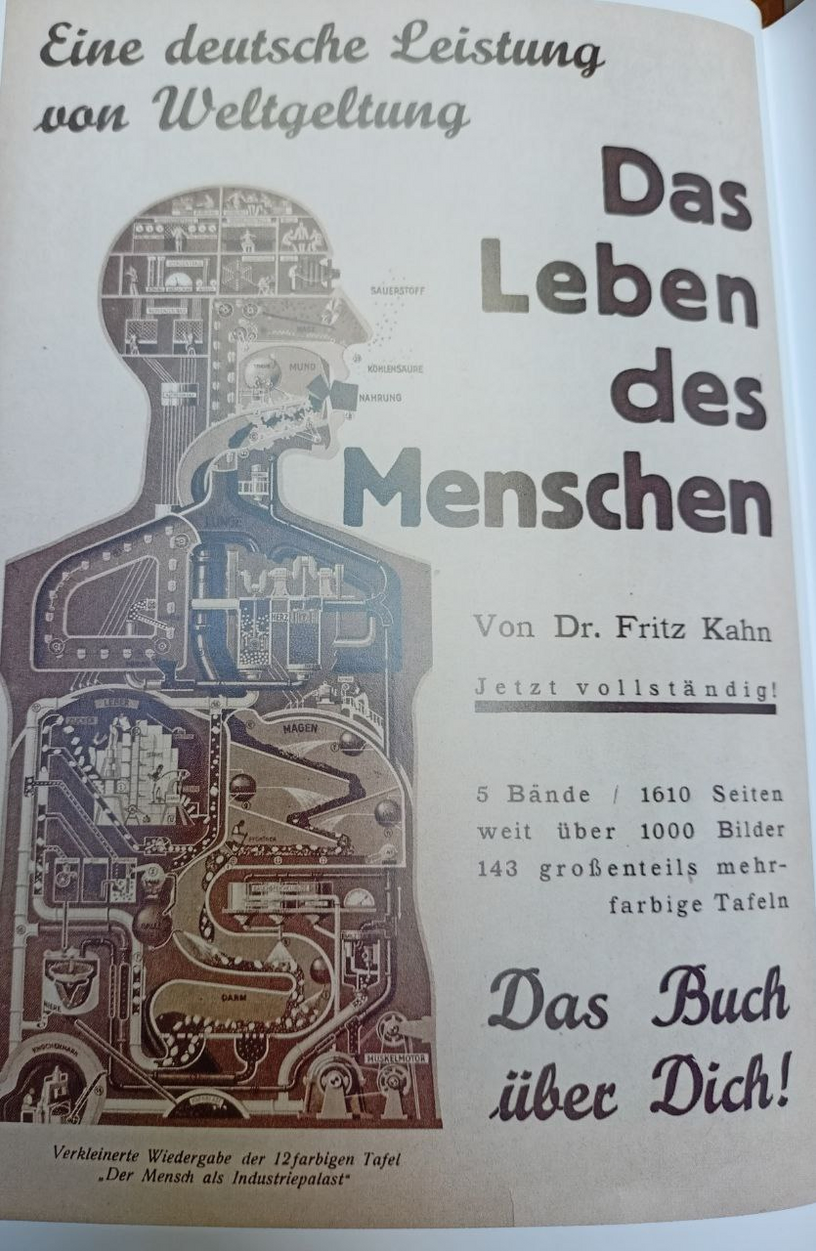

Talented scientist capable of transforming the most complex concepts into images

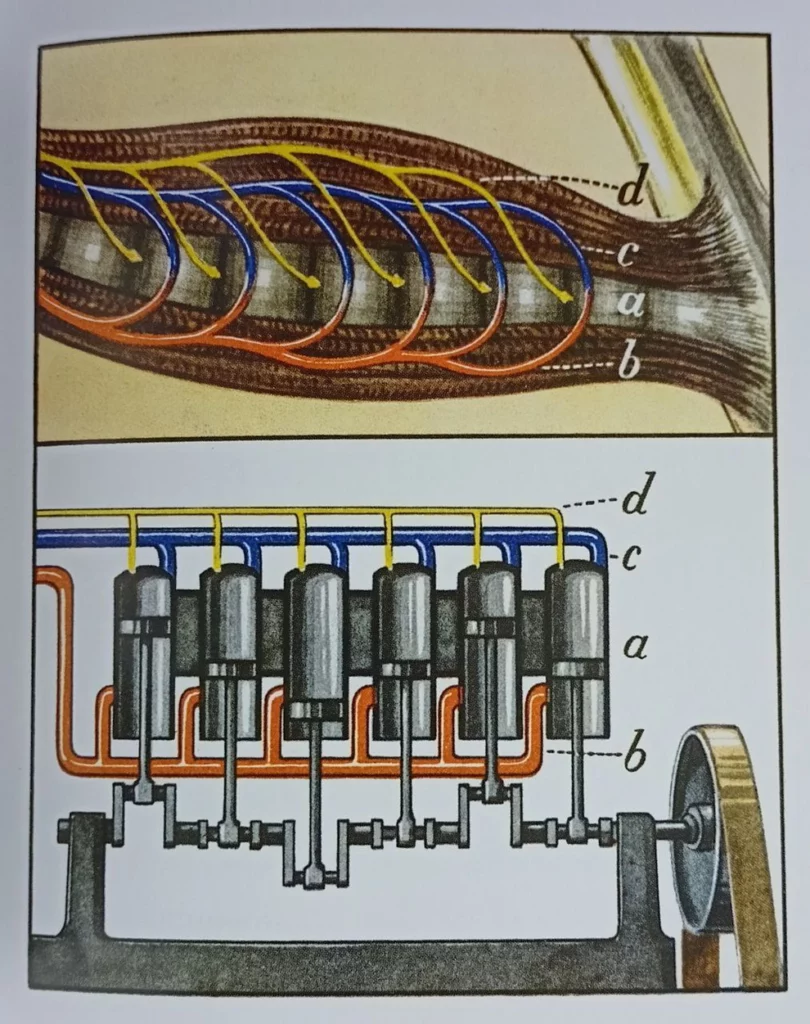

His literary success exploded with the publication of his five-volume work Das Leben Des Menschen (The Life of Man). His works are carefully illustrated with designs so particular that they become his trademark, recognizable at first glance. Many of his writings are popular science books, accessible to the general public. Fritz has a real talent for popularization: he manages to visually express complex scientific concepts, thus desecrating entire areas of biology and medicine. Many of these concepts are explained by analogy with machines or mechanisms.

Opposite, an example of a comparison between a muscle (top) and a car engine (bottom). The letter (a) designates a muscle fiber that is significantly enlarged compared to the other, allowing to detail the similarities with the piston engine.

Fritz then became a specialist in visual communication highly coveted by the press and industry.

Comparaison d'un muscle et d'un moteur de voiture.

Claiming your Jewish origins in the days of the Nazis

Fritz’s activities diversified, and he made no secret of his support for his own community: he became editor of the Encyclopaedia Judaica (Encyclopedia of Judaism), published the Sammelblätter Jüdischen Wissens (Collective files of Jewish knowledge), worked within ‘a charitable organization as well as in a hostel welcoming Jews (we are then in 1922-1931 in a Germany where the Nazi Party already exists), gives lectures and publishes scientific articles. One can note the audacity of Fritz to continue to evolve on the front of the scene in the very particular context of Nazi Germany which is then set up.

Les 7 fonctions du nez, 1939.

At the same time, Fritz is working on a book that is dear to him, as a convinced Zionist, and which concerns the natural history of Palestine (a book he will never publish, moreover) and organizes to make an expedition to the Sahara in 1932.

Censored and hunted across the world

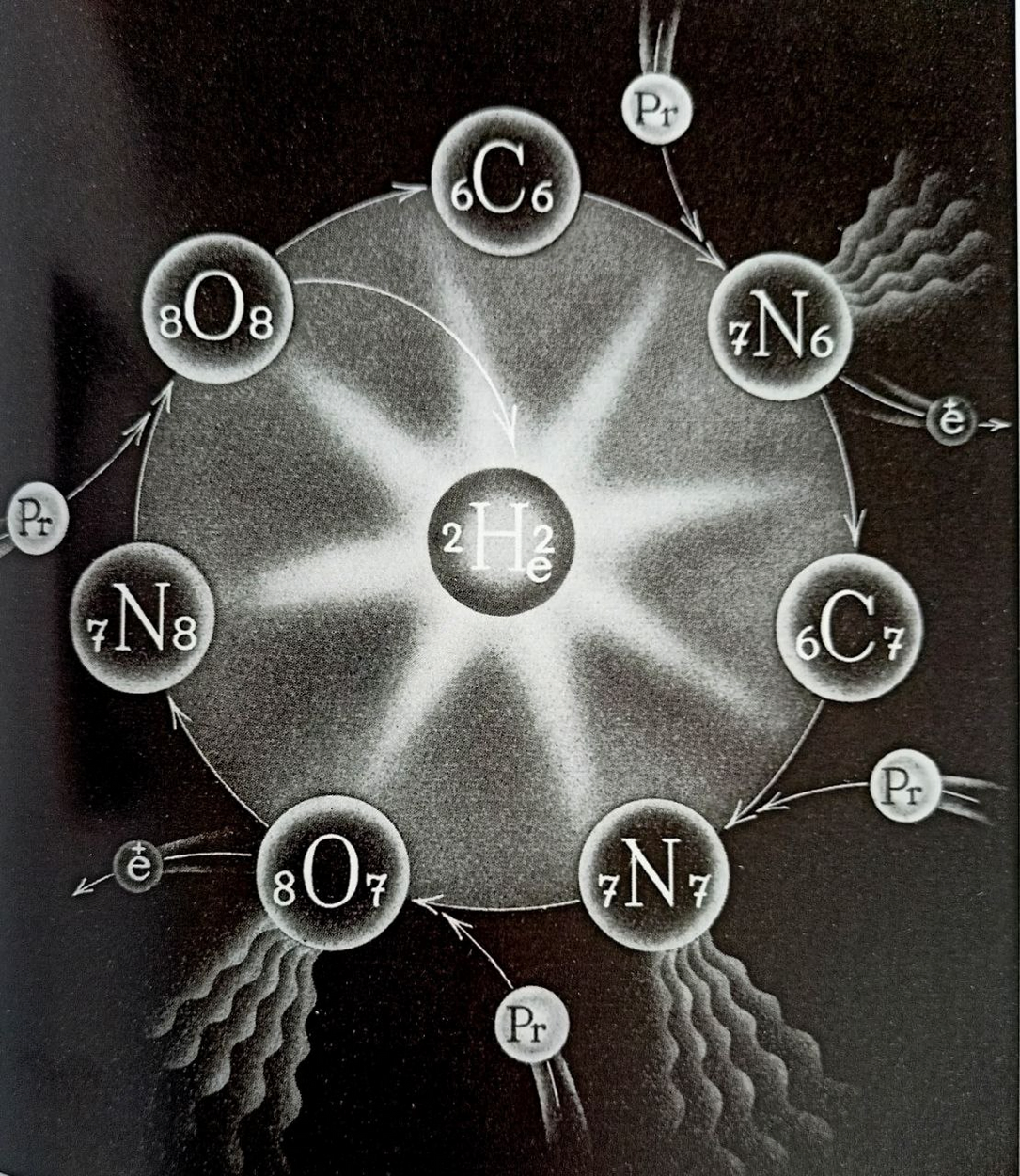

Processus cyclique dont le Soleil tire son énergie radiante selon la théorie de Bethe, 1949.

A year later, Hitler came to power and Fritz was expelled from his country. He then emigrated to Palestine with his wife Irma Glogau and their two children. He opened Hayad, a graphics and design studio in Jerusalem with his friend Eliyahu Korén, typographer and graphic artist, a German Jew who also emigrated to Jerusalem. They then work on his exhibition Hygiene of the schoolboy. At the same time, in Germany, shortly after Kristallnacht, Fritz’s books were banned, burned and placed on the list of “harmful and undesirable” writings. In addition, the Kosmos publishing house (which still exists today and was at the time known as Franckh’sche Verlagshandlung) for which Fritz worked decides to end their collaboration. But Fritz managed to get around this ban by continuing his collaboration with the Swiss subsidiary of the group, the Montana edition, then again with Kosmos (then renamed Albert Müller Verlag) in 1936, who published his best-selling book in the world: Unser Geschlechtsleben (Our sex life).

In 1937, Fritz got closer to his country by moving to France with his new wife Erna Schnadel, where he settled in the Paris region, in the affluent commune of Neuilly-sur-Seine. At that time, France was still a free country: it would only be occupied in 1940. From France, Fritz helplessly witnessed a particularly ironic violation of his copyright: Gerhard Venzmer, Nazi doctor, allows himself to illustrate his works using the images of Das Leben Des Menschen (The Life of Man), the work that Fritz had published a few years earlier and which was now banned in Germany. And it is none other than the Kosmos publishing house which allows the publication of these outrageous works! But as an exile, it is impossible for Fritz to prevent these abuses.

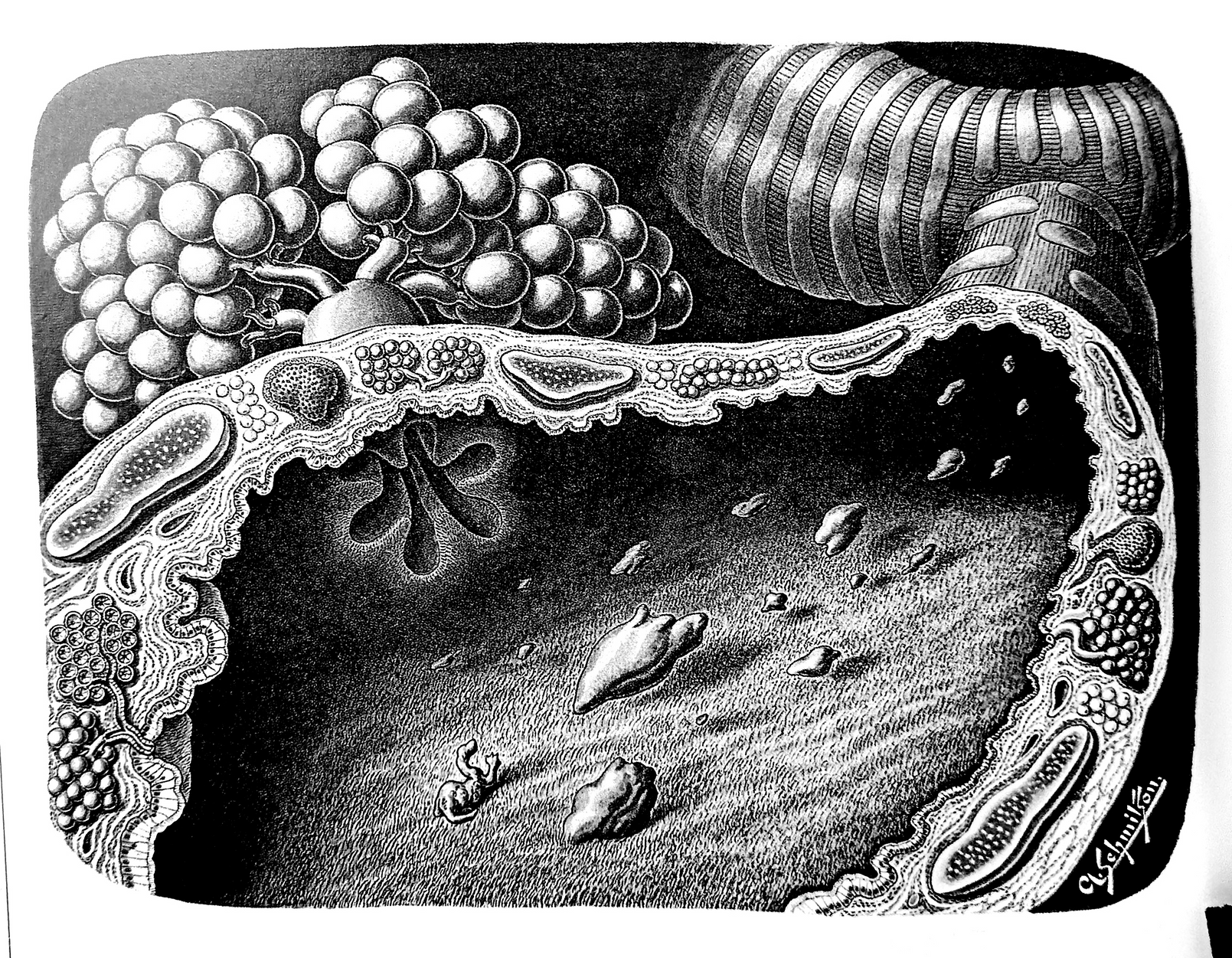

"Expériences de voyage d'une cellule mobile dans la tempête de poussières de la trachée", 1924.

Unfortunately for Fritz, the French refuge could not last very long: in 1940 the German army invaded France and Fritz was forced to flee. First in the south of France in Bordeaux, then in Spain and Portugal, before being finally welcomed in the United States thanks to the intervention of the serene Albert Einstein – himself a German Jewish scientist – and that of Varian Fry – American journalist and anti-Nazi activist – through the Emergency Rescue Committee.

A little (forced?) rest in the United States

In the United States, Fritz already has a name: some of his works (The Cell and Our Sexual Life) have been translated and widely distributed there. And thanks to the translation of L’Homme into structure and function, Frits is definitely asserting itself on the American market. But three years arrive, between 1945 and 1948, during which his collaboration with Kosmos stops: Fritz can no longer publish anything, perhaps because of the installation of the distribution of German territory between the various victors or of the trials. from Nuremberg. Still, Fritz is recovering with talent from this forced break with the publication of Das Atom (The Atom) and two other scientific books.

A little justice in this world of bullies

In 1951, at the age of 63, Fritz finally won his case in court for the damage caused by Nazi persecution through the Kosmos publishing house. Then its collaboration with Kosmos ended definitively with the retirement of its director in 1957.

A career that is running out of steam in Europe

Fritz moved to Switzerland with his third partner, Ellen Fussing. So not very happy in love, our Fritz. Some of his works continue to be republished, but his new publications do not meet with great success: his working methods and his vision of the world then seem obsolete. This did not prevent Fritz from continuing to work until his death, mainly in Denmark, where he spent the last eight years of his life. During these years, Fritz produced a brand new version of his book The Human Body, the first book where illustrations dominate the text: finally! Because we now know that a (good) picture is worth a thousand words.

Fritz died at the age of 80. If you want to immerse yourself in his innovative and creative spirit, pioneer of computer graphics, know that his ashes were scattered in Lake Maggiore, Italy.

Le Lac Majeur.

From Fritz to today, what future for computer graphics?

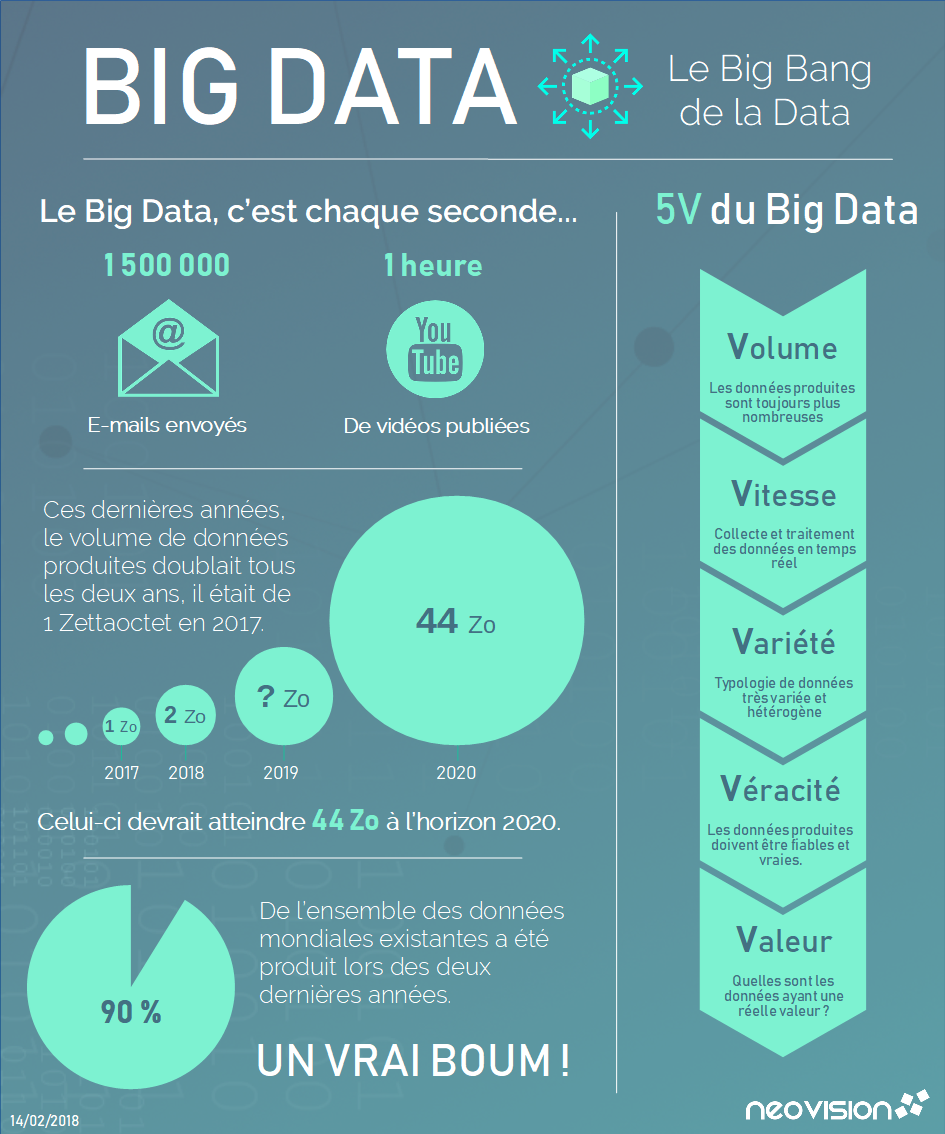

Computer graphics tend more and more towards a data visualization process. Our century has seen an explosion in the amount of digital data created: it has multiplied by 20 in ten years, and at this rate we are literally going to collapse under hard disks (except for the development of new, more compact technologies). These data come, for example, from the field of medical imaging (images produced by MRIs, scanners, etc.) or even from astrophysics (space missions, use of telescopes capable of generating 15 Tera bytes of data in one night, etc. ). This massive production of data is what is known under the soft name of Big Data (which also designates the development of technologies capable of processing this data).

But what is the point of creating data if not to analyze it? This is the main role of computer graphics: translate, synthesize and enhance raw data in order to allow analysis and communication. Nothing new compared to the work that Fritz was already doing, you tell me. But let’s just say that our entry into the era of Big Data is contributing very largely to the generalization of the use of computer graphics.

Exemple d'infographie sur le Big Data.

Les fonctions des vitamines sur 4 systèmes organiques du corps humain, Fritz Kahn, 1952.

Today there are many graphical tools that allow us to easily create infographics from data (who among us has never had to produce a graph, in Excel for example?). To name just one, Canva is an easy-to-use and fun tool that will let you create compelling visuals. But this democratization of access to computer graphics is unfortunately not accompanied by appropriate artistic training. The result is a production of infographics that are visually poor and devoid of creativity to find relevant analogies or metaphors. Drawing inspiration from artists such as Fritz can only be beneficial in sharpening our minds to designing infographics that are as relevant as they are original. So don’t interfere with your creativity and your originality, because who knows, you might just be the next Fritz Kahn!

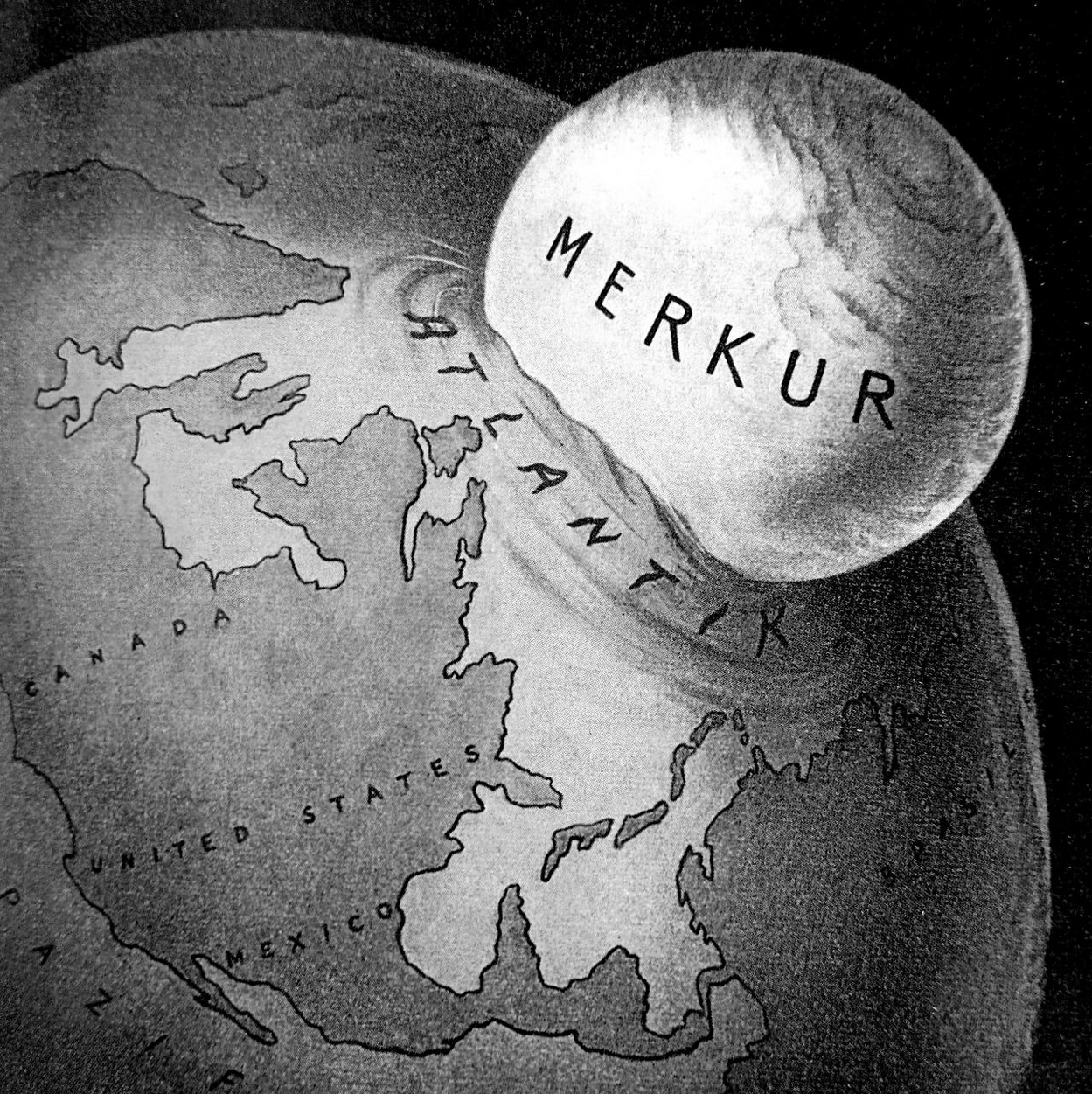

"Mercure est si petite qu'elle pourrait tomber dans l'océan Atlantique sans toucher les continents", 1952.

Crédits Images:

– Lac Majeur

– Infographie Big Data

– Livre Fritz Kahn, infographics pioneer, éditeur Taschen Bibliotheca Universalis, 2013 (un livre fabuleux, tout en images, que je recommande).

Supports:

– Thèse de Jean Charconnet, Rhétorique de la découverte et de la vulgarisation scientifique : une étude des figures de l’analogie dans le discours de la génétique, soutenue en 1999.

– L’Essentiel sur le Big Data, article publié par le CEA

– Les centres et pôles de données, CNRS

– https://www.lsst.org/